Games as a spectator sport

When I was a kid in the ancient days of the early ‘90s I was part of a church youth group. Obviously this was before I morphed into a surly, foul-mouthed teen (and then an even more profane adult). Every year the youth group would participate in an extended weekend getaway at a camp up north along with a bunch of other churches. They’d hold this little summit way up in the sticks, far removed from anything remotely resembling civilization in the middle of January during the very depths of our Canadian winter. For reasons.

Of course I went every year. Not only was it a great excuse to get an extra Friday and Monday out of school just after the Christmas break, it was always legitimately, innocently fun. It was a chance to blow off school, ditch the normal boring Sunday service, and find the most entertaining ways possible to critically injure ourselves in the woods. And in 1994 it would be even better than ever. Because that year, for whatever reason, they were holding a video game competition.

This was it, I was going to be The Wizard.

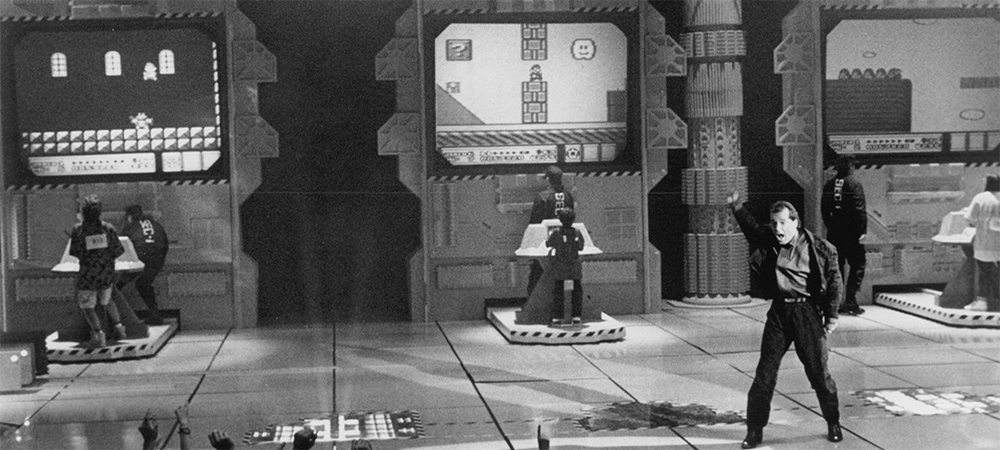

Anyone else remember the movie The Wizard? You know, that piece of shameless Nintendo product placement released to the public under the guise of entertainment? The film where we learned to “love the glove?” Well I do. Frankly, it was a real piece of shit of a movie, but I saw at an impressionable time and it will always hold a small special place in my heart.

The Wizard was a weird movie. It was a cynical exercise in co-marketing that waffled between cheesy narm and uncomfortable self-seriousness. It told the story of a traumatized autistic child but also featured a pubescent Fred Savage uncomfortably flirting with some poor 13-year-old girl. At the time though, the only message I took away from The Wizard was about being wicked sick at video games. About being so unbelievably good that people would stand up and cheer when they saw you stomp on a goomba, that they would lose their shit when you set a record lap in Radmobile. That the solution to fixing everything wrong with your life was as simple as finding the the warp whistle. I was in love with the idea.

I was never a cool kid, never popular. Even in the context of our lame-ass church youth group, I was pretty low on the old totem pole. But with this game competition I knew I’d been given a golden opportunity. I was good at games, way better than anyone else I knew. While the details about the competition were a little sketchy, the one thing they were sure of was that it would culminate with a big screen performance projected on the theater screen in the camp’s main auditorium (just like the end of The Wizard!) and the winning group would receive a brand new Sega Genesis console. This was my chance stand out and impress everyone. To win a prize for our group and be a big shot. To show them who I really was. And for better or worse, I did.

I remember being so thrilled the morning of the competition. The tournament had a weird structure. There would be some preliminary games played during the afternoon to whittle down the herd a bit (which for the life of me I can’t remember) and for the main event that evening to determine a winner, we’d be playing Sonic the mother fucking Hedgehog.

The fools were playing right into my hands.

It was like it was meant to be. Sonic was practically my best friend. I was a fucking EXPERT at Sonic. In fact, I’d already won a small competition at a local video store years ago (a story I blogged about back in the day) playing Sonic. A little piece of trivia I decided to slyly keep to myself that whole afternoon, only sharing it with a few members of my group. I let them know that so long as we made it to the finals we were good.

A few years before this, I pretty much spent a summer of my young life playing Sonic 1. It was the only game we had for the Genesis at the time and rentals for the system were scarce in my area, so I just ended up replaying it over and over again. My obsessive knowledge of the Green Hill Zone had served me before, and it looked like it was set to pay off again.

That evening we slowly filled the auditorium/theater room. The councilors, bless them, had done a really great job of making it a cool event for the kids. They’d wired up a system to play on a small monitor at the back of the room while the action was projected across a surprisingly professional movie screen for the spectators. They were even handing out bags of popcorn.

As an uber-geeky 11-year-old who practically worshiped games, seeing the Sonic title screen displayed 30 feet wide and hearing the familiar music piped through a theater sound system was practically a religious experience (I mean, probably not the one the councilors intended, but still).

They’d rigged up some kind of scoring mechanism that rewarded both time and points. Each group would pick someone to play for them and it was up to that kid to set as high a score as possible. Truth be told, I ignored them shortly into the whole explanation because I knew that in Sonic, time and points were the same thing. The person who finished the level the fastest and cleanest would always outscore everyone else, regardless of how many robots they popped or rings they collected. In fact, it seemed almost misleading to even separate the ideas (not that I was going to tell the other kids that).

We were slated to be the third group up to bat. The way the competition was set up one member of each youth group would represent their little tribe for this final confrontation, and of course I was the designated hitter. I’d talked up my Sonic skills and knew I was the one to do it, but I’d be lying if I didn’t admit to a little last minute doubt, some panic. I mean, it had already been a few years since I was really into Sonic, what if I was rusty? What if I choked? This whole thing could backfire.

As soon as I saw the first two teams take their turn, I knew how mistaken such doubts were.

Please know that I’m not trying to brag when I tell you how badly I beat the other kids. I’m not trying to hold up my skill at Sonic when I was 11 years old as some kind of point of pride. It is just the plain fact that I annihilated the other kids as soon as it was my turn. In whatever block of time they gave each of us to rack up points, I made it all the way to Robotnik, killed him, and started on the next zone before they told me to stop. None of the other kids made it that far — some of them didn’t even clear the first stage.

The worst part about it? I wasn’t even all that happy with my performance. I knew that if I had practiced I could have done A LOT better (#humblebrag before it was cool).

You have to understand, the other kids were not “gamers” like I was. They were there to play around, see the hedgehog jump over the spikes and collect a few rings. For them, the definition of being good at the game was “not dying too much”. At the height of my Sonic obsession, I was measuring success by milliseconds. It was straight up rhino versus baby stuff.

Shockingly, most of the kids weren’t exactly stoked by my performance. Instead of the cheers I expected, there was a decidedly uncomfortable atmosphere. A few scattered (begrudging) applause here and there amidst a whole lot of murmuring. Even the kids from my own youth group were kind of quiet. They were excited to win of course, but they took the temperature of the room and knew it probably wasn’t the best time to bust out in jumping jacks.

I saw a couple of the adults running the event talking to each other. I got the distinct impression they were talking about me, like this was a problem. Like they thought I cheated somehow — if not in actuality, at least in the spirit of the competition.

I was a little 11-year-old ball of indignity, utterly galled at the injustice of it. Nobody thought it was cheating earlier in the day during the Shirts and Skins basketball match (FYI, I was a Shirt by insistence) when the kids that played youth league basketball scored easy rebound after easy rebound on me. Why should they have? The basketball kids put in the work, practiced, and were (way) better at basketball than me.

But when I got a chance to take them on in the one weird arena where I excelled, suddenly it was somehow a trick? They were acting like I conned them when really I was just incredibly over-specialized at a game they were unlucky enough to turn into a competition (and yeah, I could have probably stood to branch out a bit more with my hobbies, but shut up).

In the end, our group was declared the winner. I mean, what were they going to do, say my turn didn’t count? Much to my disappointment, there was no parade. The competition just kind of petered out as the last few groups took their (pathetic) turns and shuffled off. Our youth minister took the stupid prize Sega and I never saw it again. Either he kept it for himself, or decided that video games weren’t appropriate for a religious environment, or maybe the whole boondoggle just left him with a sour taste.

After that, I was pretty sure I was doomed. I had my big chance and somehow blown it by being too good (which I thought was the whole freaking point of a competition, but what do I know). I started to wonder if there was anyone out there who loved games the way I did. This was 1994, way before I would even learn what the Internet was. The only other real game enthusiast I knew was my brother. It was the heyday of Jack Thompson and the popular idea that Mortal Kombat was turning kids into crazed serial killers. Magazines like EGM and Nintendo Power let you know you weren’t completely alone, but it all felt so far away and removed from real life. It was a weirdly lonely time to love games.

The deflated balloon of my misguided childhood dream is why I can’t get mad at modern YouTube stars who make 4 million a year screaming at the screen while they play games, no matter how much I don’t personally like the content. It’s why I don’t sneer at eSports, even when they struggle with growing pains and identity crises. It’s why I try to book days off every year in the summer to watch EVO. For as silly as it can be, I love the growth of games as a spectator event. The now-reality that people really will gather to watch talented players being wicked sick at games, to cheer them on and lose their shit with every big play and comeback. The fulfillment of The Wizard’s promise, delivered 25 years late, but finally arrived.

If an 11-year-old were to stumble on The Wizard today, he or she could take it the same way I did, but they wouldn’t be so wrong. The idea of a video game tournament people give a shit about isn’t some Hollywood fantasy anymore, it’s a daily reality. Now, The Wizard (however dated and cheesy) would play like any other movie about garage bands making it big, or underdog athletes with a lot of heart triumphing against the odds. Hollywood schmaltz of course, but the same kind that inspires some kids to pick up a guitar, or start running extra laps before school. The kind of schmaltz that sets some kids on an arc that will take them beyond dabbling in a hobby or pastime and take it further, to see if they can turn their passion into a profession.

I was too early to be The Wizard, but there is a whole generation of apprentices out there just waiting for their shot.